[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Photographs and Video by Victor Moriyama

Written by Matt Sandy

The New York Times

Brazilian Amazon

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Deforestation in the world’s largest rainforest, an important buffer against climate change, has soared under President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil

[/vc_column_text][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

RIO DE JANEIRO — When the smoke cleared, the Amazon could breathe easy again.

For months, black clouds had hung over the rainforest as work crews burned and chain-sawed through it. Now the rainy season had arrived, offering a respite to the jungle and a clearer view of the damage to the world.

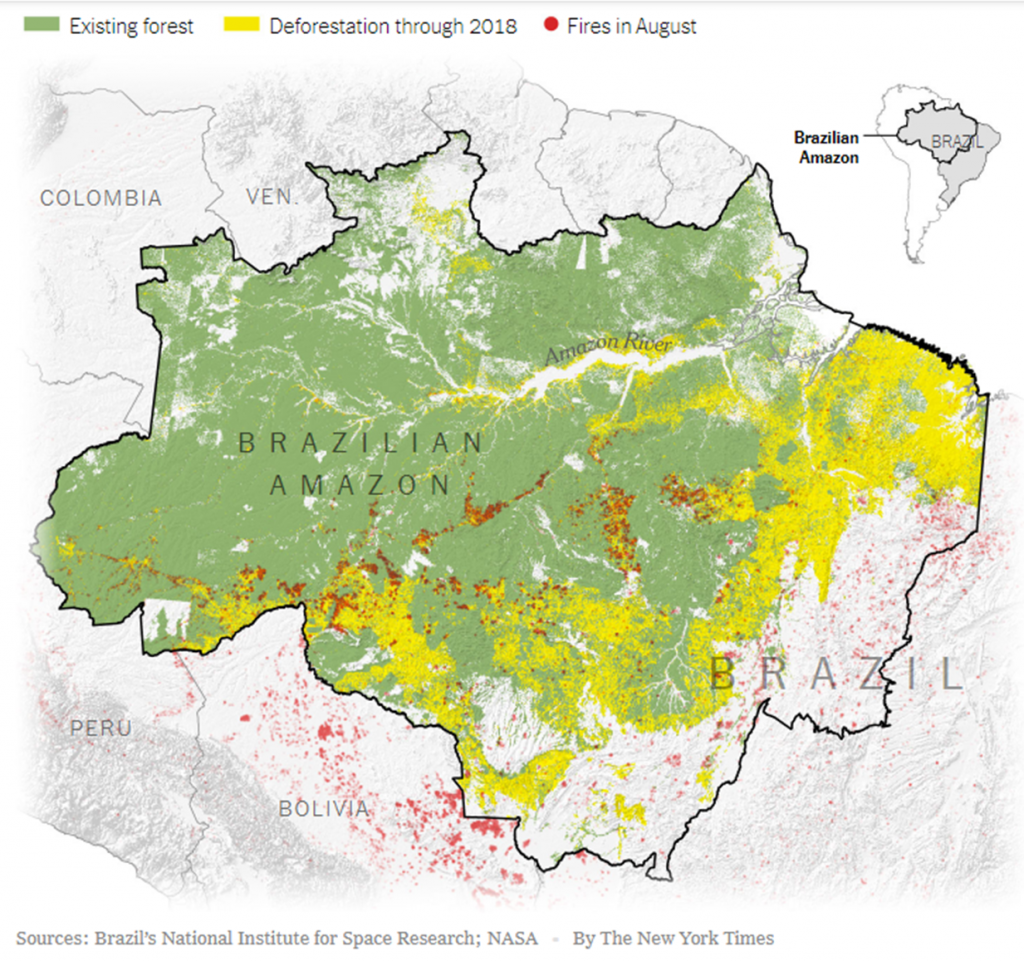

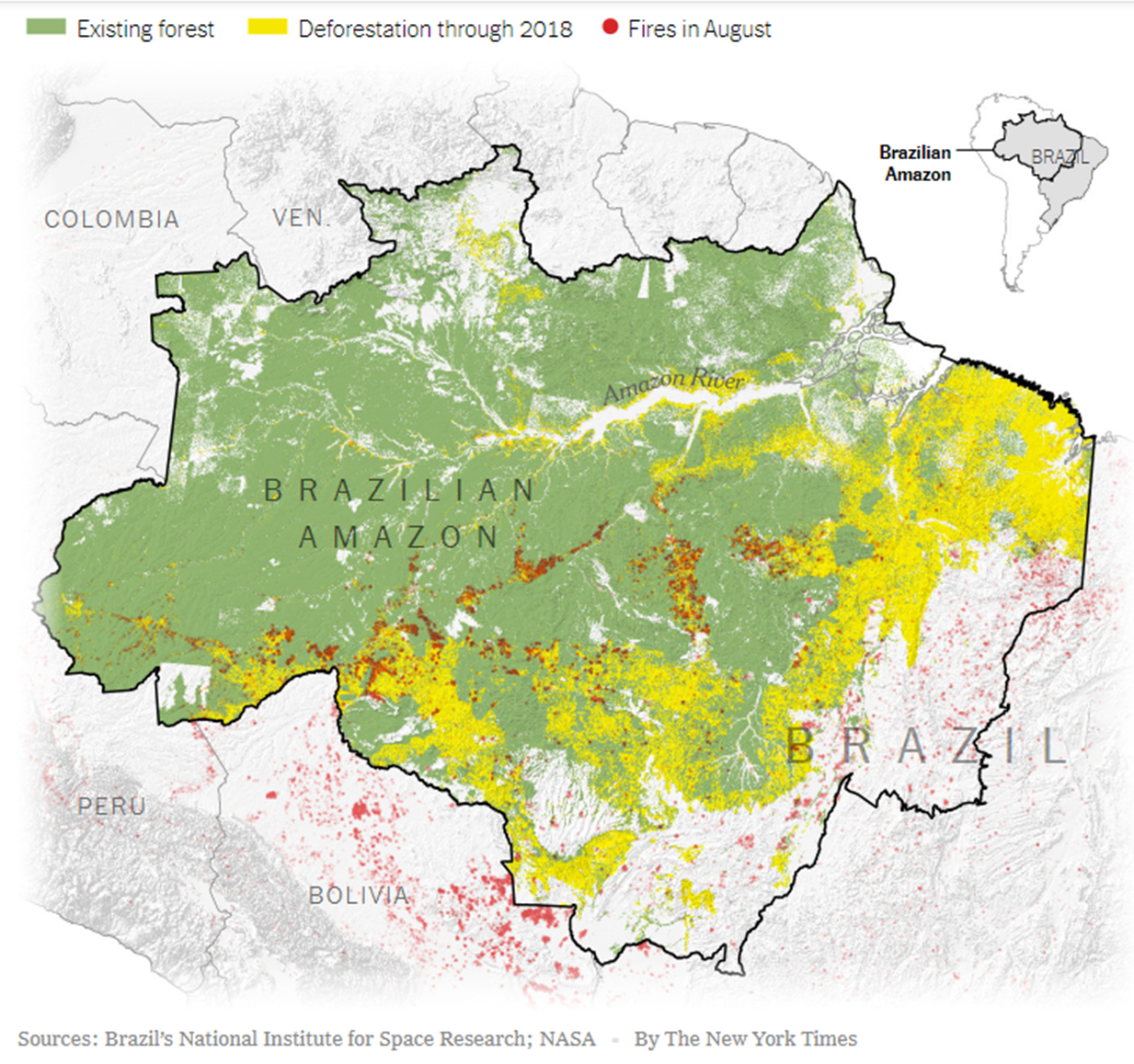

The picture that emerged was anything but reassuring: Brazil’s space agency reported that in one year, more than 3,700 square miles of the Amazon had been razed — a swath of jungle nearly the size of Lebanon torn from the world’s largest rainforest.

It was the highest loss in Brazilian rainforest in a decade, and stark evidence of just how badly the Amazon, an important buffer against global warming, has fared in Brazil’s first year under President Jair Bolsonaro.

He has vowed to open the rainforest to industry and scale back its protections, and his government has followed through, cutting funds and staffing to weaken the enforcement of environmental laws. In the absence of federal agents, waves of loggers, ranchers and miners moved in, emboldened by the president and eager to satisfy global demand.

Deforestation soared, up almost 30 percent from the year before.

“It confirms the Amazon is completely lawless,” Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist with the University of São Paulo, said of the data. “The environmental criminals feel more and more empowered.”

He warned that the Amazon may soon cross a tipping point and begin to self-destruct. “Law enforcement has reached its minimum effectiveness in a decade,” he said. “It is a worrying warning for the future.”

Mr. Bolsonaro’s government has made some nods to combating illegal clear-cutting, but the president has reaffirmed his longstanding position of disdain toward conservation work. He once said that Brazil’s environmental policy was “suffocating the country”; he vowed on the campaign trail that not “a square centimeter” of land would be designated for Indigenous people; and last month he brushed aside official data about deforestation.

His stance has been widely noted on the Amazon frontier, where the rainforest is transformed into land for cattle, soybeans and other crops in a process that can be murky, sometimes illegal and frequently violent.

Cattle on a farm as fires burn in the background near the city of União Bandeirantes in the state of Rondônia.

Cattle on a farm as fires burn in the background near the city of União Bandeirantes in the state of Rondônia.

Land being burned for cattle grazing in September in the Amazon rainforest near Porto Velho

Land being burned for cattle grazing in September in the Amazon rainforest near Porto Velho

A cattle ranch near the city of Porto Velho whose owners have used fire to expand.

A cattle ranch near the city of Porto Velho whose owners have used fire to expand.

“Deforestation and fires have always been a problem, but this is the first time it has happened thanks to the discourse and activities of the federal government,” said Marina Silva, who as environment minister in the mid-2000s cracked down on illegal activity in the Amazon, contributing to an 83 percent fall in deforestation from 2004 to 2012.

Around 2014, Brazil started sliding into a deep recession, and deforestation began to rise as ranchers and loggers searched for new land to exploit. The Amazon, relied on for centuries for rubber trees, minerals and fertile land, was the obvious place to go.

Legally harvested timber in the Caxiuanã National Forest in the state of Pará.

Legally harvested timber in the Caxiuanã National Forest in the state of Pará.

Workers suspected of illegal logging being questioned by environmental police in Pará state. Some illegal logging operations are suspected of keeping workers in conditions analogous to slavery.

Workers suspected of illegal logging being questioned by environmental police in Pará state. Some illegal logging operations are suspected of keeping workers in conditions analogous to slavery.

Workers at the sawmill in the city of Portel in Pará state.

Workers at the sawmill in the city of Portel in Pará state.

Agribusiness, always a force in Brazil, gained even more economic and political power: It now represents nearly a quarter of the country’s G.D.P., and the Amazon region supports soybean farms, gold and iron ore mines and ranches holding more than 50 million cattle.

These industries found an ally in Mr. Bolsonaro, a far-right, pro-business lawmaker before he shot to the presidency last year. His government, Ms. Silva said, “is not fighting to preserve environmental governance.”

A soybean plantation near the city of Paragominas.

A soybean plantation near the city of Paragominas.

An illegal gold mining operation deep in the Brazilian Amazon.

An illegal gold mining operation deep in the Brazilian Amazon.

A soybean plantation whose owners have used burning to expand into the Amazon rainforest near the city of Porto Velho.

A soybean plantation whose owners have used burning to expand into the Amazon rainforest near the city of Porto Velho.

Deforestation began to rise before Mr. Bolsonaro took office in January. By the height of the dry season in July and August, some experts feared that criminal loggers and ranchers, who use fire to prepare land for crops and pasture, were clearing the Amazon with impunity.

Their fires drew international attention, especially as images spread online of jungle blazes, charred trees and the smoke-darkened sky over Brazil’s largest city, São Paulo, 1,800 miles southeast of the rainforest. More than 80,000 fires were detected since the start of the year, according to government data.

A fire in September in the rainforest in the state of Rondônia.

A fire in September in the rainforest in the state of Rondônia.

Land burned to be cleared for animal agriculture in September near Porto Velho.

Land burned to be cleared for animal agriculture in September near Porto Velho.

A fire in September in the Amazon rainforest near Rio Pardo, in Rondônia state.

A fire in September in the Amazon rainforest near Rio Pardo, in Rondônia state.

The fires turned into a major diplomatic crisis for Mr. Bolsonaro, pitting him against a global backlash of politicians, celebrities and popular opinion. France threatened to block a major trade deal, and Norway and Germany halted donations to protect the rainforest.

After initially remaining defiant, Mr. Bolsonaro mobilized the military to tackle the flames and issued a decree banning fires in the Amazon for 60 days.

Brazilian environmental workers tried to prevent a fire set to expand a farm from burning out of control in September near the city of Rio Pardo.

Brazilian environmental workers tried to prevent a fire set to expand a farm from burning out of control in September near the city of Rio Pardo.

There is a climate of animosity between the local population and firefighters.

There is a climate of animosity between the local population and firefighters.

The Brazilian army accompanies the firefighting teams to ensure their safety in case of attacks by the local population.

The Brazilian army accompanies the firefighting teams to ensure their safety in case of attacks by the local population.

The furor reached such a pitch that Brazil’s businesses became worried about the potential impact. “Did we have our image harmed? Yes. Can we recover it? Yes. The government has to align its discourse to what the world wants,” said Blairo Maggi, a billionaire soybean producer and former agriculture minister known as the Soy King.

“The farmers, associations and industry will have to redo what has been lost,” he said. “We retreated 10 steps; we will have to work to get back to where we were.”

The people who work the land have expressed conflicting feelings about the deforestation. For some, the fires are a dual threat, spewing dangerous smoke and destroying a forest that has always provided a livelihood. For others, the fires create much-needed jobs, all the more valuable amid Brazil’s sluggish economy.

The Amazon jungle near Ilha do Combu.

The Amazon jungle near Ilha do Combu.

Looking for recyclable materials in the Portel city dump.

Looking for recyclable materials in the Portel city dump.

Harvesting açaí, one of the main products exported from the Amazon.

Harvesting açaí, one of the main products exported from the Amazon.

The push into the Amazon has also been driven by demand from abroad. Every year, Brazil exports nearly 15 million tons of soy, much of it to China, and more than $6 billion worth of beef — more than any other country in history. Cattle ranches account for up to 80 percent of deforested land in the Amazon, according to the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

Major beef and soy firms have been fined millions for buying commodities sourced from illegally deforested land, but such rules have proved difficult to enforce.

Roberto da Silva, a small cattle producer in Aurora Do Para.

Roberto da Silva, a small cattle producer in Aurora Do Para.

Cattle being washed before slaughter.

Cattle being washed before slaughter.

A slaughterhouse in Porto Velho. Cattle ranches account for up to 80 percent of deforested land in the Amazon.

A slaughterhouse in Porto Velho. Cattle ranches account for up to 80 percent of deforested land in the Amazon.

Last week, the environment minister, Ricardo Salles, said that the authorities needed a new strategy to stop illegal logging and mining, but he has not outlined a plan.

And despite the more conciliatory tone taken by Mr. Salles and businessmen like Mr. Maggi, Mr. Bolsonaro has again voiced an aggressive, nationalistic view of the Amazon, describing the rainforest as a resource to be exploited.

Last week, he falsely accused the actor Leonardo DiCaprio of bankrolling fires in the Amazon, and for months he has also dismissed Indigenous people’s concerns about increasing invasions of protected land by loggers and miners, even as Indigenous groups have pleaded with the government for protection from growing violence.

A burned forest area next to a cattle ranch in August in the state of Mato Grosso.

A burned forest area next to a cattle ranch in August in the state of Mato Grosso.

A legal logging crew taking down a Brazilian redwood tree in the Caxiuanã National Forest in the state of Pará.

A legal logging crew taking down a Brazilian redwood tree in the Caxiuanã National Forest in the state of Pará.

A burned area of forest adjacent to a cattle ranch in Apiacas, Mato Grosso state.

A burned area of forest adjacent to a cattle ranch in Apiacas, Mato Grosso state.

Many environmentalists directly blame Mr. Bolsonaro for the increase in deforestation, citing his firing of key officials at the main environmental regulator, IBAMA, and his refusal to endorse anti-logging operations.

“If the federal government does not profoundly change its stance on the issue,” said Mauricio Voivodic, the executive director of WWF Brasil, deforestation “will grow even more next year, causing the country to go back 30 years in terms of protecting the Amazon.”

The Amazon’s future may depend on whether that happens, with serious implications for global warming.

The rainforest stores a huge volume of carbon dioxide, which is unleashed through the fires. From January through July, deforestation and fires in the Brazilian Amazon released between 115 and 155 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions — roughly the total for the state of North Carolina — according to an analysis by the Woods Hole Research Center and IPAM-Amazônia.

“Deforestation data for the last three months also shows a very sharp increase,” said Mr. Nobre, the climate scientist.

Charcoal producers trying to put out a fire that spread from illegal burning on a neighboring cattle farm near União Bandeirantes, in Rondônia.

Charcoal producers trying to put out a fire that spread from illegal burning on a neighboring cattle farm near União Bandeirantes, in Rondônia.

A cattle ranch that uses burning to expand near the city of Porto Velho.

A cattle ranch that uses burning to expand near the city of Porto Velho.

Firefighters resting during an effort to extinguish a blaze set to clear land near Rio Pardo.

Firefighters resting during an effort to extinguish a blaze set to clear land near Rio Pardo.

Scientists also warn that decades of destruction have brought the forest close to a tipping point, in which lower rainfall and longer dry seasons would turn most of it into savanna.

According to research by Mr. Nobre, the tipping point will likely be reached at 20 to 25 percent of deforestation across the Amazon basin — or even sooner, depending on the rate of climate change. There is no accurate measure of deforestation across the nine countries containing the Amazon, but many researchers believe about 17 percent of the forest has been lost already.

Whether this year’s figures represent an acceleration of that process or an exception to the trend will only become evident next summer, when the dry season returns.

Speaking to reporters last month, Mr. Bolsonaro predicted smoke would be back with it. “Deforestation and fires will never end,” he said. “It’s cultural.”

The burning rainforest in Rondônia state in September.

The burning rainforest in Rondônia state in September.

Read the original here: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/05/world/americas/amazon-fires-bolsonaro-photos.html[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]